Are Tech Companies Overspending on AI?

Artificial intelligence has markets oscillating between excitement and trepidation. A few numbers help clarify the state of the industry.

Online searches for “AI bubble” have surged, as markets grapple with reports of extraordinary spending by the technology industry’s biggest players and their bold promise that it will lead to a fundamentally changed economy. But the bubble question is complex because it asks two things at once: what will happen to industry profits, and what will happen to stock prices? Profits, over time, reflect the durability of competitive advantages and long-term trends, while stocks are volatile, and valuation multiples can drift far from economic reality.

Therefore, to judge where an industry is headed, it’s important to look past market speculation and study what’s happening in the underlying businesses. Here are answers to key questions about the health of the businesses at the center of the AI boom.

1. Is demand for NVIDIA’s chips holding up?

Demand continues to exceed supply. NVIDIA has projected that revenue from its high-performance Blackwell and Rubin chips will exceed US$500 billion in 2025 and 2026 combined. That’s 30% higher than what the market previously expected. Overcapacity remains a theoretical concern for the chip supply chain: If AI cloud-computing demand falls short of data center operators’ plans, the industry could be left with surplus chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. However, TSMC, NVIDIA’s most critical manufacturing partner, is known for its conservative approach, typically building only about 80% of what customers request. The Taiwanese company is carefully increasing capacity at a pace that should support NVIDIA’s stated revenue goals.

2. Is competition intensifying for NVIDIA?

The reason NVIDIA has held its leadership position is that it offers the most comprehensive system of hardware and software (through its CUDA platform) for maximizing chip performance. However, competitors are making progress, and as they do, customers may prefer to diversify suppliers rather than depend solely on NVIDIA. Broadcom, for example, is strong in application-specific integrated circuits, or ASICs—chips programmed for specific tasks—and closely follows NVIDIA in chip performance; Advanced Micro Devices, though further behind, is an innovative company with growing potential. Like NVIDIA, both stand to meaningfully benefit should the broader economy embrace AI tools.

3. Are tech companies overspending on chips and data centers?

Part of what worries people about the spending on AI infrastructure is that the figures are so large. In 2026, the leading data center operators are expected to make a combined US$600 billion in capital outlays, a 30% increase over last year’s estimated sum. By McKinsey’s estimates, AI capital expenditures may total anywhere from US$3.7 trillion to US$8 trillion by 2030—though markets remain skeptical of even the low end of that projection. The wide range of potential outcomes is a reminder that the AI industry is still in its infancy and there’s no certainty about how widely the technology will be used. As companies such as Microsoft and Alphabet invest heavily in pursuit of this amorphous opportunity, one useful metric is capital intensity, or how much each spends relative to revenues.

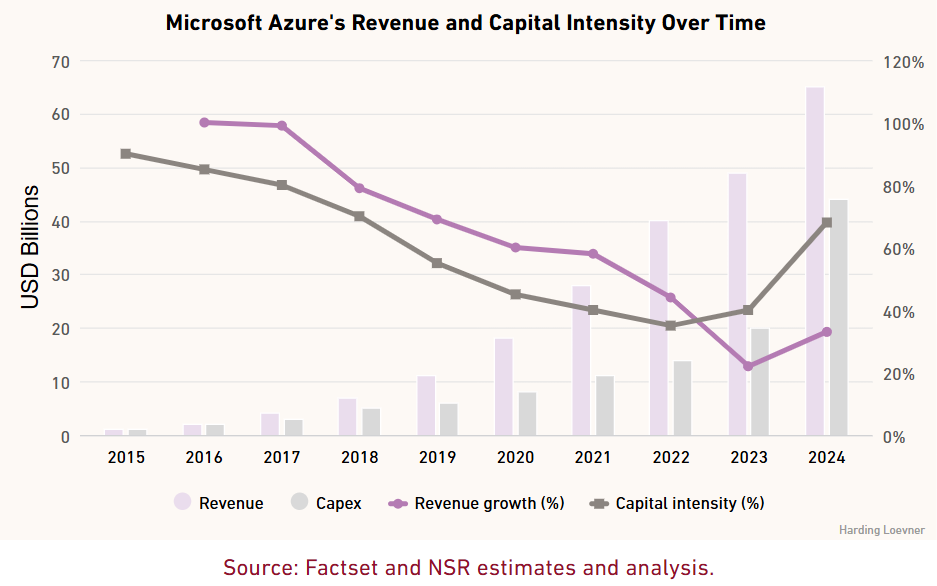

So far, it shows that AI-related spending appears to have been additive, helping to end a period of slackening growth in cloud-computing services. In the latest quarter, Microsoft said revenue in its Azure cloud business grew 39% year over year, adding that it would have been higher if not for capacity constraints. The situation was similar at Alphabet’s Google Cloud and Amazon.com’s AWS. In this sense, AI echoes the early years of cloud adoption: Heavy upfront investment in infrastructure proved beneficial because it created the capacity for future growth. For instance, when Microsoft began ramping up cloud investment in 2015, its capital intensity surged (as shown by the gray line in the chart below), but that spending laid the foundation for a long period of strong revenue (in purple).

For some, this chart reinforces fears of a bubble, because spending clearly has grown faster than revenue for the past couple years. But here’s what the totality of the data tell us so far: AI-related capex is boosting revenues, and margins remain healthy (in some cases they’re improving). The question is whether that continues. Therefore, another metric to keep an eye on is return on invested capital.

4. Aren’t AI chips only good for two and a half years?

This question reflects a shift underway at major tech companies: once primarily digital businesses, they’re now accumulating significant physical assets, which are prone to wear and tear and eventual obsolescence. Graphics processing units (GPUs) have a finite life, though it’s proving longer than many expected due to ongoing technological advances and shifting usage patterns. The transition from training AI models, which demands more processing power, to running these models to generate output (inference) has helped older GPUs retain value even after they are no longer used for training. NVIDIA’s A100 GPUs, introduced in 2020, remain in service today. Therefore, data center companies have extended their depreciation schedules to about five to six years, with the actual useful life of their GPUs likely to be even longer.

Nonetheless, non-cash depreciation expenses have risen for all the major data-center companies amid an increase in their fixed assets—chips but also servers and other networking equipment. If assets continue to be productive for longer periods though, return on invested capital should improve over time.

5. Are there strong parallels to the dotcom bubble?

Not at the company level. During the dotcom era, capital intensity rose without a corresponding increase in revenue growth. The most valuable tech companies of today are also much more profitable than those of the late 1990s, with margins exceeding 20%. It’s typical for profitability and return on invested capital to temporarily soften during periods of heavy investment. However, the exceptional profitability of companies building AI data centers distinguishes them from traditionally cyclical sectors such as Energy or Utilities, where capital intensity is similarly high but margins are persistently low.

The evolution of AI may be more akin to the rise of mobile computing, by further expanding the way computers are used and the tasks they can perform. When smartphones were introduced in 2007, they represented a step-change in performance compared to voice-only mobile phones, and for nearly a decade, the market underestimated the total demand and revenue potential of the emerging mobile ecosystem. That’s because it took some years after the breakthrough in mobile hardware for transformative applications to arrive—for example, Uber in 2010.

Therefore, AI growth is likely to be lumpy, and the timeline of any progress remains uncertain. This will make long-term forecasts more reliable than short-term valuation metrics such as price-to-earnings ratios, which can be misleading when an industry is at the top or bottom of a cycle. It’s important to model across cycles, fading assumptions about competitive advantages over time to reflect different stages of market maturity.

Big questions also remain, such as energy availability as well as future sources of financing. Spending thus far has been primarily funded by internal capital, although companies such as Meta Platforms have turned to off-balance-sheet financing and other debt. Even so, balance sheets look strong, and so with revenue moving in the right direction and margins holding up, the cycle appears to still be healthy, for now.

View the original Harding Loevner Article here.