Join the private equity party

View PDF

Everyday investors can now enjoy the higher returns and diversification normally reserved for the wealthy

Private equity has traditionally been an exclusive asset class only available to the “big end of town” and the ultra-wealthy. But, increasingly, everyday investors, including self-managed superannuation funds, are being given the chance to hop on the global private equity bandwagon.

Private equity’s popularity has grown due to several favourable characteristics, such as its historical performance across economic cycles. It allows for value creation and long-term investment horizons, as it typically doesn’t experience the same short-term fluctuations as listed equities. It also brings an “illiquidity premium” from the nature of the underlying companies, which is attractive to investors over the longer term.

More than 70% of large institutional investors allocate funds to private equity, with the average target being about 14%. Australia’s Future Fund, for example, allocates about 16.8% of its portfolio to private equity.

The growth of private companies has corresponded with a decline in publicly listed companies: for example, in 2000 there were 8090 listed US companies, yet by early 2022 this had more than halved to 3819.

Private equity provides the opportunity for inves- tors to vastly expand their universe of investable companies. Compared with those 3819 listed compa- nies in the US, there are 94,762 private companies. In Europe, there are 3824 listed developed market com- panies compared with 226,217 private companies.

Investors who only put their savings in listed companies are effectively restricting themselves to just 2% of companies in the world.

DIFFERENT STRATEGIES

Investing in private equity can take several forms. In Australia, investors tend to (incorrectly) associate private equity investing purely with venture capital – providing capital for start-ups. Yet venture capital is only one small part of many private equity strategies.

There is a private equity spectrum, from “angel investing” (providing very early seed money to start- ups) right through to distressed funding (buying the debt or assets of a distressed business and trying to return it to profitability).

But by far the most common private equity invest- ment strategies sit somewhere in between: through either buyouts or growth equity.

Buyouts are the most common private equity strategy, through either acquiring a controlling posi- tion in larger, more mature companies with estab- lished cashflows. Buyout managers utilise financial structuring and operating expertise to improve com- pany financials in order to position the company for a strategic sale at a higher valuation.

Growth equity involves building companies with solid, proven business models that are poised for further growth due to strong underlying demand, good management, a good balance sheet and a point of difference.

HOW IT HAS PERFORMED

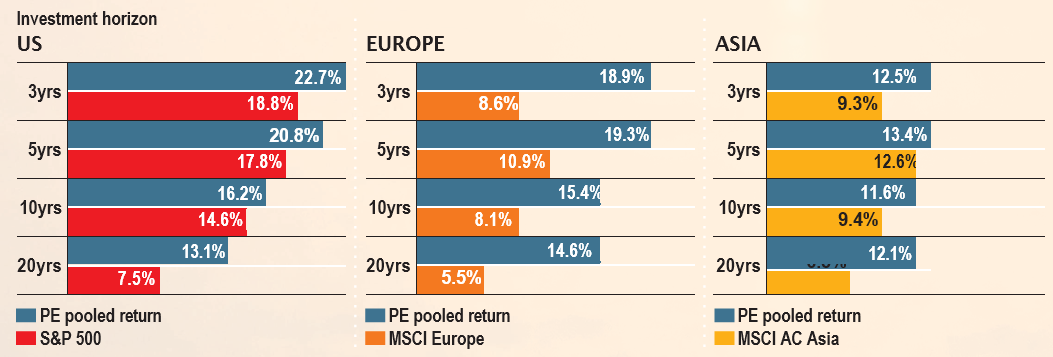

Private equity has generated compelling historical returns by outperforming its listed counterparts over multiple time horizons and across geographic regions. It has also outperformed listed equity in various economic conditions and, in particular, in periods of economic stress, such as the GFC in 2008.

With private equity having generated these higher returns at lower levels of risk (as measured by return volatility) compared to listed equities over the past 20 years, there is a potential for private equity to deliver diversification benefits to investors’ portfolios, if they are able to get past the traditionally high barriers to entry. Adding even small amounts of private equity to a portfolio can potentially increase overall returns and lessen volatility.

Private equity versus shares

THE ‘VINTAGE’ CAN COUNT

Like a good wine, the year in which private equity investments are first entered into, the vintage, can have significant influence on the end result.

Private equity has escaped the worst of the market downturn in 2022, which for equities and bonds has been worse than the first half of 2008. But private equity tends to lag equities and bonds by one or two quarters, so it could face some short-term headwinds during the second half of 2022.

Market downturns tend to have a more muted impact on the valuations for private equity than listed equities, as private equity does not experience the same big fluctuations in company valuations. Until recently, prices for listed equities have been very high compared with company earnings, yet prices for private equity buyout deals were comparatively more reasonable and stable, and therefore more appealing than listed equity counterparts, and less likely to experience severe correction.

Private equity managers can also leverage tougher market conditions to conservatively structure deals to include stronger downside protection and significant upside participation. As with timing the market, however, trying to select the best vintage can be difficult. An investor’s ability to capitalise on these vintages relies heavily on selecting the right managers, with the right connections, to do the right deals – but this raises questions around access.

INVEST FOR THE LONG TERM

Private equity is a long-term game, and its underlying access characteristics have historically been a major barrier to entry for everyday investors and even high- net-worth individuals.

It is typically accessed through newly established “primary” funds, which invest into a portfolio of underlying companies. Investors make commitments during an initial fundraising period, with the usual minimum amount of $5 million to $10 million serving as a roadblock for many investors.

The identification, due diligence and selection of managers at the outset are paramount for a successful investment: there is a clear performance gulf between the top-quartile and median private equity funds, much more so than their listed equivalents.

Gaining access to top-quartile funds is, therefore, vital to achieving consistent performance.

But it’s not easy. Not only do the best private equity managers not need your money, in many cases they don’t even want your money – the demand for their expertise is so great that many of the top-quartile managers’ new funds are oversubscribed before they even open for investment.

Many private equity funds have a life of 10 years or more, although some investments may see some realisations after five to seven years. They are specifically structured to be illiquid.

Even high-net-worth individuals struggle to create their own sufficiently diversified private equity portfolios – a well-structured, diversified private equity program may require upwards of $100 million in capital, considering the high minimum investment to access a single fund manager.

Private equity firms with capital to deploy are able to buy distressed assets at attractive prices

HOW TO GAIN ACCESS

Until recently, private equity has really been the domain of the uber wealthy or big institutional investors, such as the Future Fund.

But everyday investors are starting to gain access.

In 2019, Pengana Capital Group announced a partnership with the US-based GCM Grosvenor, a $US71 billion ($105 billion) private equity powerhouse, to launch the ASX-listed Pengana Private Equity Trust (PE1).

This solves the access issues, with everyday and self-managed super fund investors now able to invest in a diversified portfolio of global private equity, with low barriers to entry and daily liquidity made availa- ble through an ASX-listed investment trust structure.

The trust offers investors a single point of entry to a global portfolio of more than 400 underlying private companies, with an expectation that this will further increase to more than 500 over time, as new primary funds are added the underlying portfolio.

The trust is further diversified through exposure to deals across economic cycles that span from 2003 to the present day, and has utilised a range of private equity strategies and implementation methods. It focuses on the middle market – companies with enterprise values of $US500 million to $US1.5 billion, and avoids investments in venture capital.

The trust recently reported a net return of 26.7% for 2021-22. Since inception to June 30, 2022, it has delivered a 13.4%pa net return on its net asset value.

THEY LOVE A RECESSION

More companies are choosing to remain in private hands, yet they may still require capital. They still need to refresh their shareholder base, and they need to expand their businesses, which has the potential to provide an enormous opportunity for investors who can access this part of the market.

There’s a saying in private equity circles: “private equity managers love a good recession”. Recent history has shown that while private equity has outperformed listed equity across all stages of the economic cycle, this effect is magnified during, and immediately following, recessionary periods.

Historically, private equity firms with capital to deploy are able to buy distressed and/or undervalued assets at attractive prices.

Middle-market companies are currently particularly attractive in private equity because they have a broader range of exit options, including trade sales, management buyouts or sales to other private equity funds. They don’t need to rely on initial public offerings (IPOs), which is a good thing, as IPOs have dropped off this year. The other great advantage of middle-market companies is the ability to secure favourable terms for additional rounds of venture capital raising.

Private equity has been particularly active in recession-resistant industries, such as consumer staples, healthcare and utilities, which are holding up relatively well. Continued outperformance will likely depend on targeting pockets of stability and opportunity alongside the right managers, with a focus on profitable companies in defensive and attractive industries including consumer staples, government services, IT, logistics and healthcare.

Russel Pillemer is CEO of Pengana Capital Group.